“I was compelled to love you, not because you are the fairest, but because you are the deepest, for a lover of mere beauty is usually a fool”

– Mahmoud Darwish (1941-2008).

Coming out of the spiritual and traditional holds of the conventional genres of poetry, the late 18th and 19th centuries provided for a poetic movement that was dedicated whole-heartedly towards the interior worlds of feeling, in opposition to the mannered formalism and disciplined scientific enquiry of the enlightenment era that preceded it. This movement is what is termed as Romanticism. Poets like Mary Shelley, Mary Robinson, Charlotte Turner Smith, William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, John Keats, Percy Shelley, William Blake, Lord Byron, and so on, are huge examples of this ideology of literature, and produced works that expressed spontaneous feelings, found parallels to their emotional lives in the natural world, and celebrated creativity rather than logic.

The spirit of Romanticism wasn’t just to counter the ideology upheld by the Enlightenment era, rather it was majorly dedicated to celebrating the creativity of life and emotions by the use of metaphors and paralleling the natural world with human emotions, and love being the epitome of the same. Nature is a substantial presence in Romantic poetry, functioning as a teacher and companion. The poets viewed their art as mediation between humanity and nature and would set their human dramas on her stage. The Romantic wanderer and vicariously the reader would learn his or her place in the universe by journeying through nature’s dark spaces and exotic dream lands. The mysterious, monstrous, and strange are all Romantic era poetic predilections.

This romantic era emphasised intuition and imagination over reason, everyday language over inscrutable poetic form, and the pastoral over the urban. Imagination is the gateway to transcendence, and the poet filters powerful emotions and emotive responses, translating them into an accessible poet form. The arguably extreme idealism of Romanticism was characterised by a search for immortality, imperfections and pure love, in parlance with everyday life.

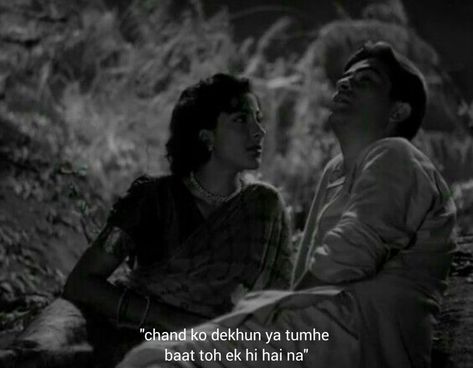

The Sky: An Eternal Muse for Poets

The sky has been an eternal muse for poets and artists alike, its endless expanse serving as a captivating metaphor for the depth and breadth of love. The sky’s vastness evokes a sense of infinity, mirroring the boundless nature of the love that we feel for another. The clouds that dance across the sky are akin to the ebbs and flows of a relationship, representing moments of turbulence as well as serenity. The sunrise and sunset, in all their resplendence, capture the start and end of a love story, embodying the promise of new beginnings and the acceptance of closure. The stars that shimmer in the night sky, like diamonds in the firmament, symbolise the fleeting yet profound moments of happiness shared with our beloved. The moon, in all its mystique and enchantment, encapsulates the magic and transformative power of love, illuminating our path to finding meaning and purpose. Ultimately, the sky reminds us of the universality of love, a force that binds us together and gives our lives greater meaning.

Indeed, the sky continues to inspire and captivate us, with its ever-changing hues and moods. The shifting shades of blue and pink during dawn and dusk reflect the nuances of love, its shades and intensities. The wispy clouds that adorn the sky, taking on a myriad of shapes and forms, are reminiscent of the playful and whimsical nature of love. The thundering clouds and lightning bolts that occasionally pierce the sky are akin to the challenges and obstacles that we must navigate in a relationship. And yet, just as the sky eventually clears after a storm, so too can love endure and thrive despite the challenges that may arise.

Moreover, the sky’s beauty and majesty serve as a reminder of the power of love to transcend our individual selves and connect us to something greater than ourselves. The vastness of the sky reminds us that our love is but a small yet significant part of the grand tapestry of life, a testament to the beauty and wonder of the universe. Whether it is the quiet stillness of a starry night or the vibrant hues of a sunset, the sky is a canvas that reflects the myriad emotions and experiences that love brings into our lives. It is a reminder that love is not just a feeling, but a journey that takes us to new horizons, enriching our lives and elevating our souls.

Flowers: A Reminder that Eternal Beauty and Love are Inseparable

Flowers have long been revered as one of nature’s most exquisite creations, a symbol of love and beauty that transcends cultures and time. Each petal, delicate and intricate, is a testament to the wonder and complexity of life. The vibrant colors that adorn flowers, ranging from soft pastels to bold hues, evoke a sense of vitality and passion that is reminiscent of the intensity of love.

Like love, flowers have the power to transform us, to uplift our spirits and bring joy to our hearts. Their sweet fragrance and gentle sway in the breeze evoke a sense of calm and serenity, reminding us to appreciate the simple pleasures of life. The different varieties of flowers, each with its own unique beauty and symbolism, offer a rich tapestry of emotions and experiences that are akin to the nuances of love.

From the dainty and fragile beauty of a rose to the robust and hearty sunflower, flowers represent the diversity and complexity of love. The intricacy of a lily, with its soft petals and complex patterns, captures the depth and richness of love’s many layers. The velvety texture of a carnation, with its vibrant colours and sweet scent, embodies the sensual and passionate nature of love.

In essence, flowers are a metaphor for love, a reminder that beauty and love are inseparable. They remind us that even in the darkest moments, there is always beauty to be found, a ray of hope that can light up our lives. They remind us that love is not just an emotion, but a force that can inspire us to be our best selves, to see the world in a new and beautiful way. Whether it is a single bloom or a fragrant bouquet, flowers remind us of the power and magic of love, a force that can transform our lives and touch our souls.

Air: An Ethereal Metaphor of Love

The air that surrounds us, invisible yet all-pervading, is a poetic and ethereal metaphor for love. Just as the air is essential to sustain life, so too is love necessary to nourish the soul. The gentle breeze that caresses our skin, cool and refreshing, represents the comfort and warmth that love brings to our hearts.

The air can also be unpredictable and tempestuous, like the ups and downs of a relationship. The winds that gust and swirl, tugging at our hair and clothes, mirror the turbulence and challenges that love can bring. But just as the air eventually calms and settles, so too can love endure and thrive despite the difficulties.

Moreover, the air is a reminder of the intangible yet powerful nature of love. Just as we cannot see or touch the air, so too is love a force that transcends the physical realm. It is a feeling that fills our hearts and souls, giving us the strength and courage to face the world. The air is also a symbol of freedom and liberation, a reminder that love is not meant to be possessive or suffocating. Like the air that allows birds to soar and clouds to drift, love should give us the space and freedom to grow and evolve as individuals.

In essence, the air is a beautiful and evocative metaphor for love, reminding us of the delicate yet enduring nature of this powerful emotion. Whether it is the gentle breeze that cools our skin or the gusting winds that challenge us, the air reminds us that love is a force that can bring us to greater heights and give us courage to embrace life to the fullest.

Clouds: The Ebb and Flow of Love

The clouds that drift lazily across the sky are a poetic and enchanting metaphor for love, evoking a sense of wonder and mystery. Like love, clouds come in a multitude of forms and shapes, each one unique and breathtaking in its own way. The delicate wisps of a cirrus cloud, high and wispy, embody the ethereal and intangible nature of love, while the dramatic and imposing form of a cumulonimbus cloud reflects the power and intensity of this complex emotion.

Clouds also have the ability to transform and shape the world around us, much like the way love can alter and shape our lives. The gentle puffs of a cumulus cloud can cast dappled shadows on the ground, creating a sense of enchantment and magic that is reminiscent of the joy and wonder that love can bring. The looming form of a thundercloud, with its dark and ominous presence, is a stark reminder of the challenges and obstacles that love can pose.

Furthermore, the movement of clouds across the sky serves as a metaphor for the ebb and flow of love. Just as clouds drift and move across the sky, so too can love evolve and change over time. The shifting hues of a sunset or the vivid colours of a sunrise, reflected on the clouds, remind us of the endless possibilities and beauty that love can bring.

In essence, clouds are a beautiful and evocative metaphor for love, capturing the complexity and wonder of this powerful emotion. Whether it is the delicate and ethereal wisps of a cirrus cloud or the imposing and dramatic form of a cumulonimbus cloud, the clouds remind us that love is a force that can shape and transform our lives, leaving an indelible mark on our hearts and souls.

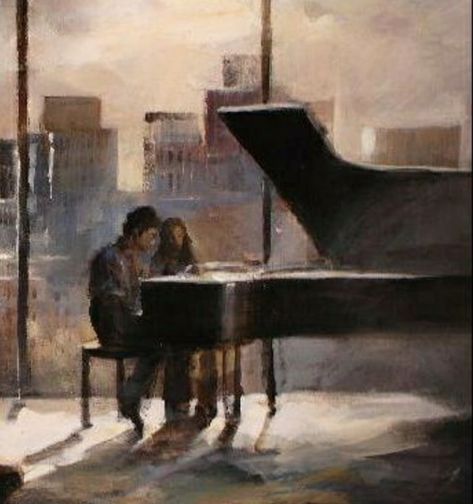

Romanticism: A Melody that Stirs Our Heart

Romanticism is the heartbeat of the soul, the melody that stirs our hearts and fills us with a sense of wonder and awe. It is the brushstroke that paints our world with beauty and colour, the spark that ignites our passion, and the fire that drives our dreams. Through romanticism, we connect with the world around us on a deeper level, embracing the complexities and nuances of life with a sense of reverence and awe. It is the force that moves us, the inspiration that drives us forward, and the foundation upon which our most cherished memories are built.

Romanticism infuses our days with meaning and purpose, reminding us of the beauty and majesty that surrounds us at every turn. It is the laughter that bubbles up from within us, the tears that we shed, and the joy that fills our hearts. It is the promise of a new beginning, the hope that fuels our dreams, and the faith that sustains us through the darkest of times.

In essence, romanticism is the soul of our existence, the essence of our being that connects us to the world around us. It is the light that illuminates our path, the magic that makes our hearts sing, and the wonder that fills our days with joy and delight. Without romanticism, life would be a mere existence, a hollow shell of what it could be. But with romanticism, we soar to greater heights, embracing the wonder and beauty of life in all its splendour.

-Aaditya Bajpai