What is Art? Well, there are two main definitions. Number 1 is any human creative endeavour, whether literature or music or anything else. Number 2 is more specific – the “visual arts”. But the trouble with that second definition of Art, the type we imagine in galleries and museums, is that it never really existed. Galleries and museums are beautiful places for sure, but they can easily make us forget that art almost always had a specific context.

They might make it seem like art doesn’t have a setting or an objective, both of which are important to understand. That is to say, it wasn’t made with the intention of being shown in a museum where it would be seen, examined, and evaluated as “Art” in isolation. The Benin Bronzes, for example, which can be seen in collections all over the globe, provide a clear illustration of this phenomenon. These were made in the Kingdom of Benin (present-day Nigeria) between the 13th and 18th centuries to serve as palace decorations and as a cultural chronicle of the kingdom’s history.

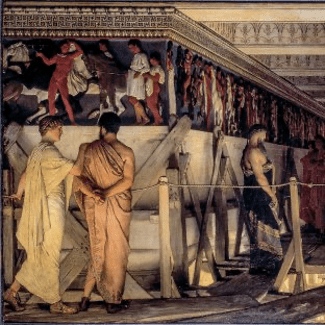

This is also true of the Parthenon Friezes, created in about 440 BC by the sculptor Phidias to decorate the brand-new Parthenon in Athens, a temple at the heart of the city. It wasn’t just “art”; it had a place and a function, a symbolic and religious meaning.

There are less egregious examples. Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam, from about 1511, is one of the world’s most famous images. But it was painted on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, a place of religious worship. Seen on its own in cropped images, such context is lost.

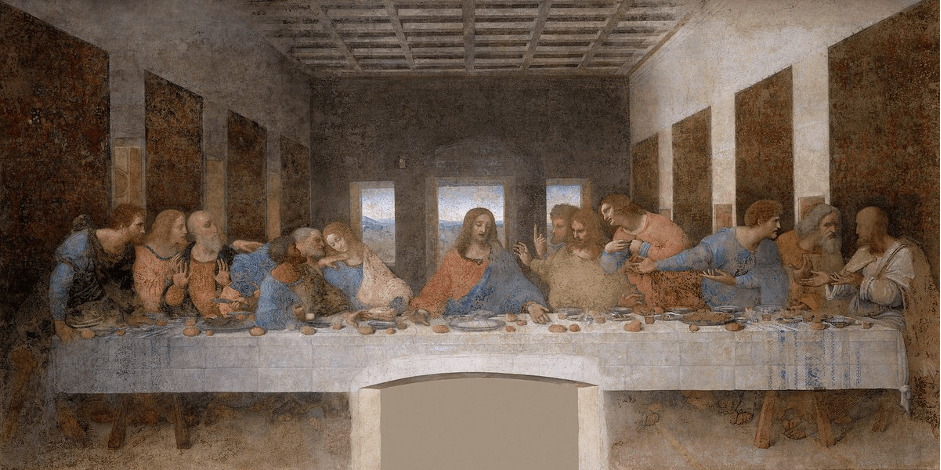

Leonardo’s Last Supper, immortalised in popular culture, is another case in point. This is the image we are accustomed to seeing:

But, in the 1490s, Leonardo painted it on the walls of a refectory in Milan. This was a dining room where the monks of the convent would come together to eat, with Jesus and the apostles eating right alongside them.

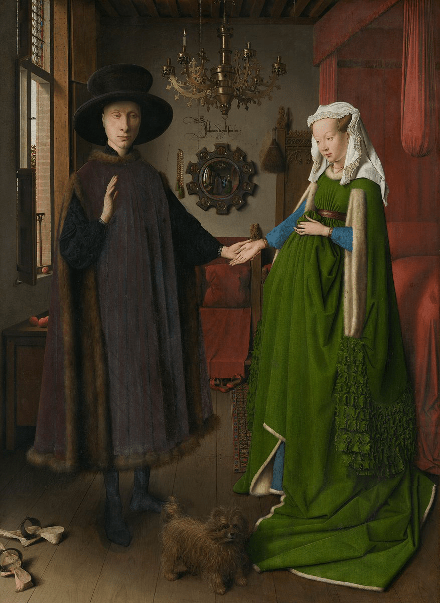

It even goes for portraits. Like Jan van Eyck’s masterful Arnolfini Portrait, created in 1434 to mark the marriage between an Italian merchant called Giovanni Arnolifini and his wife. Which would then have a place in the couple’s home to remember the occasion of their wedding.

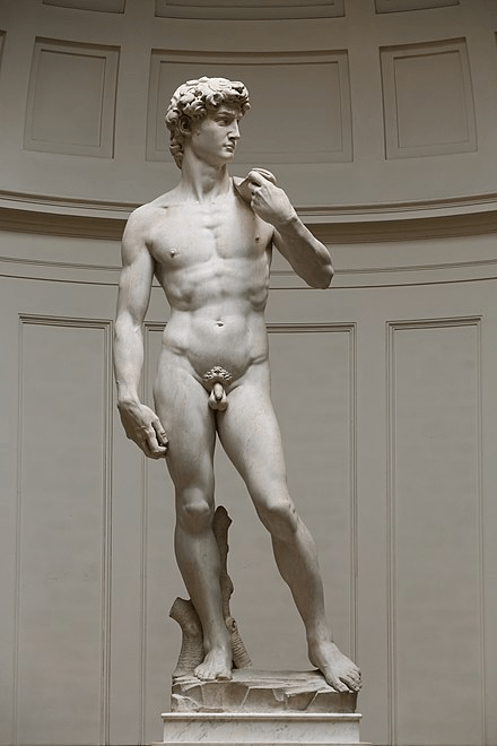

Michelangelo’s David was originally commissioned to be placed on the roof of Florence Cathedral. But it was too heavy to haul up, so they placed it outside the Palazzio Vecchio in 1504, Florence’s town hall, with that famous gaze directed towards Rome, Florence’s rival.

And it was only in 1873 that David was moved to his current location in the Galleria dell’ Accademia. Still a symbol of Florentine identity, of course, but somewhat shorn of the original political-artistic statement he once made.

And then, on a smaller scale, are the great Gothic works of art like the Wilton Diptych, painted in the 1390s for the personal use of King Richard II of England in prayer and worship. This art wasn’t for art’s sake; it had a function.

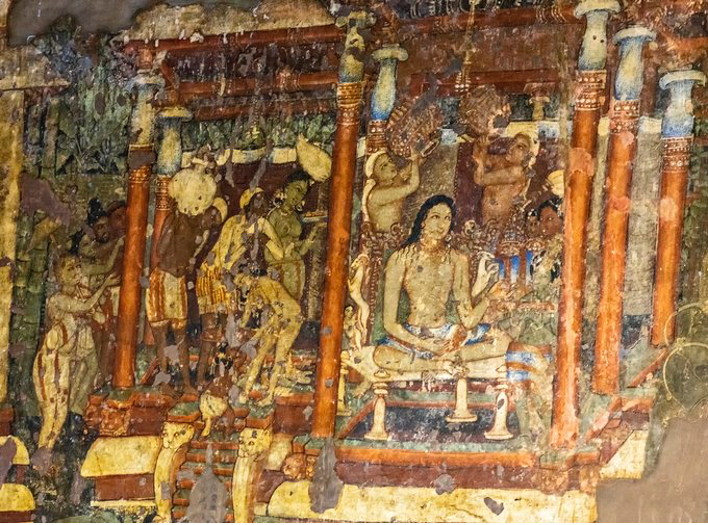

While the wonderful Ajanta Murals, painted between about 200 BC and 600 AD in the astonishing rock-cut temples and chambers in Maharashtra, India, record the life of the Buddha, his followers, his teachings. They weren’t just made to be pretty; they told an important story.

In the the 17th and 18th centuries the “vedutisti”, led by Canaletto, produced magnificent, highly-detailed cityscapes. But these were a sort of pre-photographic souvenir for tourists (usually rich Englishmen in those days) to take home as a memory of the places they’d visited.

The point here isn’t that art can’t be enjoyed or loved or appreciated without knowledge of its original purpose. Indeed, the mark of all truly great art is to exceed its context and reach a sort of universal truth or beauty which speaks to us directly. But it’s important to remember the link between art and its socio-cultural context; that humanity’s creative endeavours have always had a purpose. Seen in galleries or simply as images we are in danger of separating “art” from the rest of human civilisation.

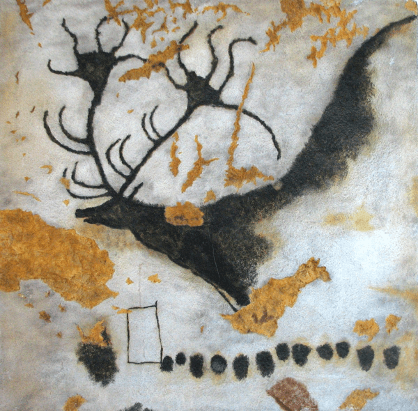

What might we imagine was the purpose of the oldest art we know? We can never be sure what prehistoric cave paintings like those in Lascaux, France, from 19,000 years ago, were intended for. But we can guess!

Because, even though it’s been millennia, we’re still doing the same thing. Why do individuals go through the trouble of decorating their homes? It’s possible that this was the same motivation that drove our ancestors to decorate the cave walls all those years ago. Art not only honors and symbolizes significant events, but it also serves to remind us that we are beings of meaning in addition to biological make-up. Because of this, even the most well-known works of art have a distinct function and setting, whether it be Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper displayed beside the monks at lunchtime or the colorful magnets on your refrigerator. It is not something that exists separate from society; rather, it is an integral element of society. Take for example, the question of whether or not the Statue of Liberty may be considered a work of art. Obviously, this is the case, but there is also “more” to it. Imagine it displayed in a gallery or a museum behind a glass case, similar to how the Benin Bronzes or the Parthenon Friezes are shown.

Doesn’t seem quite right, does it?

This post is uploaded and detailed by The CULTURAL TUTOR on TWITTER.

CHECK HERE